By Sam Rainsy,

In my article in The Geopolitics on May 13, “Why Southeast Asia Is Relatively Spared by COVID-19”, I presented the cases of five countries in Southeast Asia (Cambodia, Laos, Vietnam, Thailand and Burma) and compared them with the five Western countries most seriously affected by the coronavirus (France, Italy, Spain, the UK, the US).

I noted four factors which could explain why the five Southeast Asian countries seem relatively well protected from the COVID-19 pandemic: a climate factor related to the temperature, an economic and demographic factor linked to lifestyles and the age of the population, an immunity factor related to malaria and a genetic factor linked to hemoglobin E.

I will now extend my comparisons to India and then Africa to test these hypotheses.

India

Like Southeast Asia, India has been relatively spared by COVID-19. At 15 May the country officially had 2,753 deaths in a population of 1.378 billion, or two deaths per million people. The figure compares with 345 deaths per million on average for the five big Western countries worst hit by COVID-19.

The first two hypotheses, concerning climate, and economics and demography, help to explain the mildness of COVID-19 in India and Southeast Asia. These two factors appear to be widely recognised and accepted.

I want to verify the relevance of my third hypothesis concerning immunology and malaria.

The Indian average of two deaths per million people covers wide disparities between different regions and states in the sub-continent. The regions and states where malaria is endemic, that is the centre-east and the north-east, are very little affected by COVID-19, with less than 0.5 deaths per million people. Other regions and states which do not have malaria are more affected by the coronavirus. This is notably the case for Maharashtra (the darkest area on the map) in the centre-west, which has had nine deaths per million inhabitants.

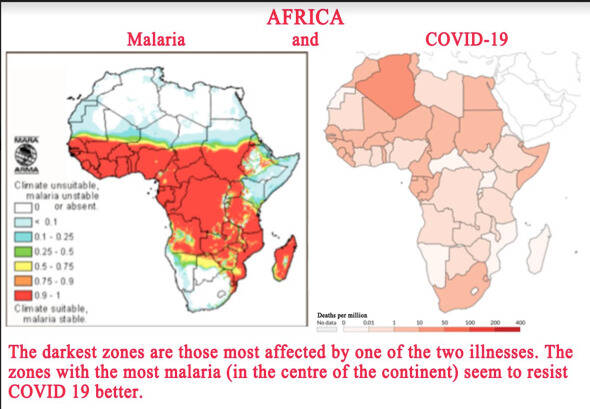

Africa

The same point can be made for Africa, which also seems to be relatively spared by COVID-19, with two deaths per million inhabitants, the same mortality rate as in India. Again, this rate varies considerably from one region to another: the north and the south of Africa, which are far from the continent’s malaria zones, have suffered worse from COVID-19 than the central part of the continent, where the prevalence of malaria seems to protect populations from the coronavirus.

One of the most interesting cases concerns Sudan and South Sudan. These two states were a single country until 2011. Since separation, their border corresponds almost exactly to the limits of malaria. Until 14 May, South Sudan, which is in the malaria zone, had no deaths from COVID-19, while Sudan, sheltered from malaria, already around 100 deaths.

Hemoglobin E

One region of India offers the chance to verify the fourth hypothesis for why Southeast Asia has been relatively spared: the genetic factor connected to the hemoglobin E present in the blood of the region’s populations. I have put forward the hypothesis that hemoglobin E may protect the populations that possess it from malaria as well as from COVID-19. The populations of Northeast India next to Burma have this blood characteristic. It should be noted that the presence of hemoglobin E is considered in India as a blood disorder, as it is very rare in the rest of the country.

The seven small states of Northeast of India, probably due to their historical, geographical and ethnic ties with neighbouring Burma, have all four of the epidemiological characteristics of Southeast Asia as far as COVID-19 is concerned. It is therefore not surprising that Southeast Asia and Northeast India have the world’s lowest mortality rates, virtually nil at 0.1 to 0.2 deaths per million inhabitants.

Under-evaluation

It could be argued that such low mortality rates in Southeast Asia and Northeast India may be due to under-evaluation of fatal cases in the official statistics. Some fatal cases might not have been reported. To an extent this could be true without changing the fact that COVID-19 has had only a light impact in the two regions concerned, and for specific reasons. If the pandemic had caused deaths in much greater numbers, this would have been noticed, as the countries concerned have very different political and social systems. It would have been difficult to hide or falsify reality in such a uniform way.

For the time being, trying to understand the resistance to COVID-19 in some parts of the world – notably through enquiries into immunological and genetic factors – consists of no more than simple observations. Whether resistance to malaria strengthens resistance to COVID-19 and whether hemoglobin E does indeed offer protection against the two illnesses are questions that I hope will one day be answered. I hope that examination of these questions will lead to research which will help us to better understand the coronavirus and contribute to the development of both a vaccination and a treatment.

Ajouter un commentaire

Commentaires